# Alteza [](https://pypi.org/project/alteza/) [](https://github.com/arjun-menon/appletree/actions/workflows/type-checks.yml/) [](https://github.com/arjun-menon/appletree/actions/workflows/test-run.yml/)

Alteza is a static site generator<sup>[<img height="10" width="10" src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/8/80/Wikipedia-logo-v2.svg/103px-Wikipedia-logo-v2.svg.png" />](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Static_site_generator)</sup> driven by [PyPage](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage).

Examples of other static site generators can be [found here](https://github.com/collections/static-site-generators).

Alteza can be thought of as a simpler and more flexible alternative to static site generators like [Jekyll](https://jekyllrb.com/), [Hugo](https://gohugo.io/), [Zola](https://www.getzola.org/), [Nextra](https://nextra.site/), etc.

The differentiator with Alteza is that the site author (if familiar with Python) will have a lot more

fine-grained control over the output, than what (as far as I'm aware) any of the existing options offer.

The learning curve is also shorter with Alteza. I've tried to follow [xmonad](https://xmonad.org/)'s philosophy

of keeping things small and simple. Alteza doesn't try to do a lot of things; instead it simply offers the core crucial

functionality that is common to most static site generators.

Alteza also imposes very little _required_ structure or a particular "way of doing things" on your website (other than

requiring unique names). You retain the freedom to organize your website as you wish. The name _Alteza_ comes from

a word that may be translated to [illustriousness](https://m.interglot.com/en/es/illustriousness) in Español.

A key design aspect of Alteza is writing little scripts and executing such code to generate your website. Your static

site can contain arbitrary Python that is executed at the time of site generation. [PyPage](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage),

in particular, makes it seamless to include actual Python code inside page templates. (This of course means that you

must run Alteza with trusted code, or in an isolated container. For example, in a [GitHub action–see instructions below](#github-action).)

## User Guide

1. The directory structure is generally mirrored in the generated site.

2. By default, nothing is copied/published to the generated site.

* A file must explicitly indicate using a `public: true` variable/field that it is to be published.

* Therefore, directories with no public files do not exist in the generated site.

* Files _reachable_ from marked-as-public files will also be publicly accessible.

* Here, reachability is discovered when a provided `link` function is used to link to other files.

* All files starting with a `.` are ignored.

3. All file and directory names, except for index page files, _at all depth levels_ must be unique. This is to simplify use of the `link(name)` function. With unique file and directory names, one can simply link to a file or directory with just its name, without needing to disambiguate a non-unique name with its path. Note: Directories can only be linked to if the directory contains an index page.

4. There are two kinds of files: **static asset** files, and **PyPage** (i.e. dynamic *template/layout* or *content*) files. PyPage files get processed by the [PyPage](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage) template engine.

5. **Static asset** files are **_not_** read by Alteza. They are _selectively_ either **symlink**ed or **copied** to the output directory (you can choose which, with a command-line argument). Here, _selectively_ means that they are exposed in the output directory _only if they are linked to_ from a PyPage file using a special Alteza-provided `link(name)` function.

6. PyPage files are determined based on their file name extension. They are of two kinds:

1. **Markdown** files (i.e. files ending with `.md`).

2. Any file with a `.py` before its actual extension (_i.e. any file with a `.py` before the last `.` in its file name_). These are **Non-Markdown Pypage files**.

7. There is an inherited "environment"/`env` (this is just a collection of Python variables) that is injected into the lexical scope of every PyPage file, before it is processed/executed by PyPage. This `env` is a little different for each PyPage invocation--a copy of the inherited is `env` is created for each PyPage file. More on `env` in a later point below.

8. **Non-Markdown Pypage files** are simply processed with PyPage as-is (and there is no template application step for non-Markdown PyPage files). The `.py` part is removed from their name, and the output/result is copied to the generated site.

9. **Markdown** files:

1. Markdown files are first processed with PyPage, with a copy of the inherited `env`.

2. After this, the Markdown file is converted to HTML using the [Python-Markdown](https://python-markdown.github.io/reference/) library.

3. Third, they have their "front matter" (if any) extracted using the Python-Markdown's library [Meta-Data](https://python-markdown.github.io/extensions/meta_data/) extension/feature.

1. The first line with a `---` in the Markdown file ends the front matter section.

2. The front matter is processed by Alteza as YAML using the [PyYAML](https://pyyaml.org/wiki/PyYAML).

4. The fields from the YAML front matter the fields are injected into the `env`/environment.

5. The HTML is injected into a `content` variable in `env`, and this `env` is passed to a `layout` **template** specified _in configuration_, for a second round of processing by PyPage. (Note: PyPage here is invoked on the template.)

1. Templates are HTML files processed by PyPage. The PyPage-processed Markdown HTML output is passed to the template/layout as the `content` variable. The template itself is then executed by PyPage.

2. The template/layout should use this `content` value via PyPage (with `{{ content }}`) in order to inject the `content` into itself.

3. The template is specified using a `layout` or `layoutRaw` variable declared in a `__config__.py` file. (More on configuration files in a later point below.)

4. A `layout` variable's value must be the name of a template.

1. For example, you can write `layout: ordinary-page` in the YAML front matter of a Markdown file.

2. Or, alternatively, you can also write `layout = "ordinary_page"` in a `__config__.py` file. If a `layout` variable is defined like this in a `__config__.py` all adjacent and descendant files will inherit this `layout` value.

1. This can be used as a way of defining a _**default**_ layout/template.

2. Of course, the default can be overridden in a Markdown file by specifying a layout name in the YAML front matter, or with a new default in a descendant `__config__.py`.

3. Lastly, alternatively, a `layoutRaw` can also be defined whose value must be the entire contents of a template PyPage-HTML file. A convenience function `readfile` is provided for this. For example, you can write something like `layout = readfile('some_layout.html')` in a config file. A `layoutRaw`, if specified, takes precedence over `layout`. Using this `layoutRaw` approach is not recommended.

5. Layouts/templates may be overridden in descendant `__config__.py` files. Or, may be overridden in the Markdown file _**itself**_ using YAML front matter (by specifying a `layout: ...`), or even in a PyPage multiline code tag (not an inline code tag) inside a PyPage file (with a `layout = ...`).

6. Markdown files result in **_a directory_** with the base name (_i.e. without the `.md` extension_), with an `index.html` file containing the Markdown's output.

10. The **Environment** (`env`) and **Configuration** (`__config__.py`, etc.):

1. _Note:_ Python code in both `.md` and other `.py.*` files are run using Python's built-in [`exec`](https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#exec) (and [`eval`](https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#eval)) functions, and when they're run, we passed in a dictionary for their `globals` argument. We call that dict the **environment**, or `env`.

2. Configuration is done through file(s) called `__config__.py`.

1. First, we recursively go through all directories top-down.

2. At each directory (descending downward), we execute an `__config__.py` file, if one is present. After execution, we absorb any variables in it that do not start with a `_` into the `env` dict.

3. The deepest `.md`/`.py.*` files get executed first. After it executes, we check if a `env` contains a field `public` that is set as `True`. If it does, we mark that file for publication. Other than recording the value of `public` after each dynamic file is executed, any modification to `env` made by a dynamic file are discarded (and not absorbed, unlike with `__config__.py`).

* I would not recommend using `__config__.py` to set `public` as `True`, as that would make the entire directory and all its descendants public (unless that behavior is exactly what is desired). Reachability with `link` (described below) is, in my opinion, a better way to make _only reachable_ content publicly exposed.

11. The **Name Registry** and the **`link`** function.

1. The name of every file in the input content is stored in a "name registry" of sorts that's used by `link`.

1. Currently, names, without their file extension, have to be unique across input content. This might change in the future.

2. The Name Registry will error out if it encounters any non-unique names. (I understand this is a significant limitation, so I _might_ support making this opt-out behavior with a `--nonunique` flag in the future.)

2. Any non-dynamic content file that has been `link`-ed to is marked for publication (i.e. copying or symlinking).

3. A Python function named `link` is injected into the top level `env`.

1. This function can be used to get relative links to any other file. `link` will automatically determine and return the relative path to a file.

* For example, one can do `<a href="{{link('some-other-blog-post')}}">`, and the generated site will have a relative link to it (i.e. to its directory if a Markdown file, and to the file itself otherwise).

2. Reachability of files is determined using this function, and unreachable files will be treated as non-public (and thus not exist in the generated site).

3. This function can be called both with a string identifying a file name, or with a reference to the file object itself. `link` will check the type of the argument passed to it, and appropriately handle each type.

4. This `link` function can also be called with string arguments using wiki-style links in Markdown files. For example, a `[[Happy Cat]]` in a Markdown file is the equivalent of writing `[Happy Cat]({{link('Happy Cat')}})`, or of writing `<a href="{{link('Happy Cat')}}">Happy Cat</a>`.

4. A file name's extension must be omitted while using `link` (including the `.py*` for any file with `.py` before its extension).

* i.e., e.g. one must write `link('magic-turtle')` for the file `magic-turtle.md`, and `link('pygments-styles')` for the file `pygments-styles.py.css`.

* Directories containing index files should just be referred to by the directory name. For example, the index page `about-me/hobbies/index.md` (or `about-me/hobbies/index.py.html`) should just be linked to with a `link('hobbies')`.

12. #### Expected (and Optional) Special Variables/Functions

Certain fields, with certain names, hold special meaning, and are called/used by Alteza. One such variable is `layout` (and `layoutRaw`), which points to the layout/template to be used to render the page (as explained in earlier points above). It can be overriden by descendant directories or pages.

#### Built-in Functions and Fields

<table>

<tr>

<th>Built-in</th>

<th>Description</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><code>link</code></td>

<td>

The `link` function takes **a name** or an object, and returns _a **relative** link_ to it. If a name is provided, it looks for that name in the NameRegistry (and throws an exception if the name wasn't found).

The `link` function has the side effect of making the linked-to page publicly accessible, if the page that is creating the link is reachable from another publicly-accessible page. The root `/` index page is always public.

_Note:_ for Markdown pages, an extra `../` is added at the beginning of the returned path to accommodate the fact that Markdown pages get turned into directories with the page rendered into an `index.html` inside the directory.

Availability:

<table>

<tr>

<td>Page</td>

<td>Template</td>

<td>Config</td>

<td>Index</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="center">✅</td><td align="center">✅</td><td align="center">❌</td><td align="center">✅</td>

</tr>

</table>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><code>path</code></td>

<td>

The `path` function is similar to the `path` function above, except that:

* it _**does not**_ have the side effect of impacting the reachability graph, and making the linked-to page publicly accessible, and

* it also does not add an extra `../` at the beginning of the returned path for Markdown pages.

This function is good for use inside templates, to reference parent/ancestor templates for injection. For example, writing something like `{{ inject(path('skeleton')) }}`.

Available everywhere.

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><code>dir</code></td>

<td>

The `dir` variables points to a `DirNode` object representing the directory that the relevant file is in.

This object has a fields like `dir.pages`, which is a list of all the pages (a list of `PageNode` objects) representing all the pages in that directory. Pages means Markdown files and HTML files. Some of the fields in `dir` are:

1. `dir.subDirs`: List of `FileNode` objects of files in this directory.

2. `dir.files`: List of `FileNode` objects of files in this directory.

3. `dir.pages`: List of `PageNode` objects of Markdown files, non-Markdown PyPage files, and HTML files.

4. `dir.indexPage`: A `PageNode` object of the index page, i.e. a `index.md` or a `index.html` file. If there is no index page, this is `None`.

5. `dir.title`: A string `title` object of the index page, only if the index page specifies a title. If there is no index page or no title specified by it, this is `None`.

In templates, the `dir` points to the directory that the file being processed is in.

Available everywhere.

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Title</td>

<td>The title is accessed with <code>page.title</code>. It is picked up either from PyPage code in the page or a <code>title</code> YAML field in the file. If `title` is not defined by the page, then <code>page.realName</code> of the file is used, which is the adjusted name of the file without its extension and idea date prefix (if present) removed. The title isn't <em>properly</em> available to Python inside the page itself, or from <code>__config__.py</code>, since the page has not been processed when these are executed. If <code>page.title</code> is accessed from these (the page or config), or if a <code>title</code> was never defined in the page, then the <code>.realName</code> of the file would be returned.

Note: the title can directly be accessed as `title` (without `pageObj.title`) in the template (and [inherited](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage?tab=readme-ov-file#inheritance-with-inject-and-exists) templates) for the page, since all environment variables from the page are passed on to the template, during template processing.

Availability:

<table>

<tr>

<td>Page</td>

<td>Template</td>

<td>Config</td>

<td>Index</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="center">❌</td><td align="center">✅</td><td align="center">❌</td><td align="center">✅</td>

</tr>

</table>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>YAML fields & other vars</td>

<td>

YAML fields (and other variables defined in PyPage code) of a page are:

* Available directly to template(s) that the page uses/invokes.

* Stored in `pageObj.env`, for future access. The index page, for example, can use `page.env` to access these fields & variables.

* Stored _**as attributes**_ in the `PyPageNode` page object, as long as the `env` var does not conflict with an existing attribute of `PyPageNode`.

* This enables referring to a field or variable with just `page.fieldName` (instead of having to write `page.env[fieldName]`, which is also valid).

<br />

Availability (same as `title`):

<table>

<tr>

<td>Page</td>

<td>Template</td>

<td>Config</td>

<td>Index</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td align="center">❌</td><td align="center">✅</td><td align="center">❌</td><td align="center">✅</td>

</tr>

</table>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Last Modified Date & Time</td>

<td>

_This is only available on `PageNode` objects._

The last modified date & time for a given file is taken from:

a. The date & time of _the last commit that modified that file_, in git history, if the file is inside a git repo.

b. The last modified date & time as provided by the file system.

There's a `getLastModifiedObj()` function which returns a Python `datetime` object. There's also a `getLastModified(f: str = default_datetime_format)` functon which returns a `str` with the date & time formatted.

The `default_datetime_format` is `%Y %b %-d at %-H:%M %p`.

_Note:_ This function calls spawns a `git` process, so is a tiny bit slow.

Available everywhere.

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Idea Date</td>

<td>

_This is only available on `PageNode` objects._

The "idea date" for a given file is either:

a. For a Markdown file, a date prefix before the markdown file's name, in the form `YYYY-MM-DD`.

b. If not a Markdown file or there's no date prefix, and _the file is in a git repo_, then the idea date is the date of the first commit that introduced the file into git history. (Note: this breaks if the file was renamed or moved.)

c. If there is neither a date prefix and the file is not in a git repo, there is no idea date for that file (i.e. it's `None` or `""`).

There's a `getIdeaDateObj()` function which returns a Python `date` object (or `None` if there's no idea). There's also a `getIdeaDate(f: str = default_date_format)` functon which returns a `str` with the date & time formatted or `""` if there's no idea date.

The `default_date_format` is `%Y %b %-d`.

_Note:_ This function calls spawns a `git` process, if it's not a Markdown file or if there is no date prefix in the Markdown file's name.

Available everywhere.

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><code>readfile</code></td>

<td>This is just a simple built-in function that reads the contents of a file (assuming <code>utf-8</code> encoding) into a string, and returns it.

Available everywhere.

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><code>sh</code></td>

<td>This exposes the entire <code>sh</code> library. The current working directory (CWD) would be wherever the file being executed is located (regardless of whether the file is a regular page or index page or <code>__config__.py</code> or template). If the file is a template, the CWD would be that of the page being processed.

See `sh`'s documentation here: https://sh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

Available everywhere.

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td><code>skip</code></td>

<td>This environment variable, if specified, is a list of names of files or directories to be skipped. (It must be of type <code>List[str]</code>, if defined.)

</td>

</tr>

</table>

## GitHub Action, Installation & Command-Line Usage

### GitHub Action

Alteza is available as a GitHub action, for use with GitHub Pages. This is the simplest way to use Alteza, if you intend to use it with GitHub Pages. Using the GitHub action will avoid needing to install or configure Alteza. You can easily create & deply an Alteza website onto GitHub Pages using this action.

To use the GitHub action, create a workflow file called something like `.github/workflows/alteza.yml`, and paste the following in it:

```yml

name: Alteza

on:

workflow_dispatch:

push:

branches: [ "main" ]

jobs:

build:

name: Build Website

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: read

pages: write

id-token: write

environment:

name: github-pages

url: ${{ steps.generate.outputs.page_url }}

steps:

- name: Generate Alteza Website

id: generate

uses: arjun-menon/alteza@v0.9.1

with:

path: .

```

The last parameter `path` should specify which directory in your GitHub repo should be rendered into a website. Also, note: make sure to set the `branches` for `workflow_dispatch` correctly (to your branch) so that this action is triggered on each push.

For an example of this GitHub workflow above in action, see [alteza-test](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza-test) ([yaml](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza-test/blob/main/.github/workflows/alteza.yml), [runs](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza-test/actions/workflows/alteza.yml)).

### Installation

You can [install](https://docs.python.org/3/installing/) Alteza easily with [pip](https://pip.pypa.io/en/stable/):

```

pip install alteza

```

Try running `alteza -h` to see the command-line options available.

### Running

If you've installed Alteza with pip, you can just run `alteza`, e.g.:

```sh

alteza -h

```

If you're working on Alteza itself, then run the `alteza` module itself, from the project directory directly, e.g. `python3 -m alteza -h`.

### Command-line Arguments

The `-h` argument above will print the list of available arguments:

```

usage: __main__.py --content CONTENT --output OUTPUT [--clear_output_dir] [--copy_assets] [--seed SEED] [--watch]

[--ignore [IGNORE ...]] [-h]

options:

--content CONTENT (str, required) Directory to read the input content from.

--output OUTPUT (str, required) Directory to write the generated site to.

--clear_output_dir (bool, default=False) Delete the output directory, if it already exists.

--copy_assets (bool, default=False) Copy static assets instead of symlinking to them.

--seed SEED (str, default={}) Seed JSON data to add to the initial root env.

--watch (bool, default=False) Watch for content changes, and rebuild.

--ignore [IGNORE ...]

(List[str], default=[]) Paths to completely ignore.

-h, --help show this help message and exit

```

As might be obvious above, you set the `--content` field to your content directory.

The output directory for the generated site is specified with `--output`. You can have Alteza automatically delete it entirely before being written to (including in `--watch` mode) by setting the `--clear_output_dir` flag.

Normally, Alteza performs a single build and exits. With the `--watch` flag, Alteza monitors the file system for changes, and rebuilds the site automatically.

The `--ignore` flag is a list of _paths_ to files or directories to ignore. This is useful for ignoring directories like `.gitignore`, or other non-pertinent files and directories.

Normal Alteza behavior for static assets is to create symlinks from your generate site to static files in your content directory. You can turn off this behavior with `--copy_assets`.

The `--seed` flag is a JSON string representing seed data for PyPage processing. This seed is injected into every PyPage document. The seed _is not global_, and so cannot be modified between files; it is copied into each PyPage execution environment.

To test against `test_content` (and generate output to `test_output`), run it like this:

```sh

python -m alteza --content test_content --output test_output --clear_output_dir

```

## Development & Testing

Feel free to send me PRs for this project.

### Code Style

I'm using `black`. To re-format the code, just run: `black alteza`.

Fwiw, I've configured my IDE (_PyCharm_) to always auto-format with `black`.

### Type Checking

To ensure better code quality, Alteza is type-checked with five different type checking systems: [Mypy](https://mypy-lang.org/), Meta's [Pyre](https://pyre-check.org/), Microsoft's [Pyright](https://github.com/microsoft/pyright), Google's [Pytype](https://github.com/google/pytype), and [Pyflakes](https://pypi.org/project/pyflakes/); as well as linted with [Pylint](https://pylint.pycqa.org/en/latest/index.html).

To run some type checks:

```sh

mypy alteza # should have zero errors

pyflakes alteza # should have zero errors

pyre check # should have zero errors as well

pyright alteza # should have zero errors also

pytype alteza # should have zero errors too

```

Or, all at once with: `mypy alteza ; pyflakes alteza ; pyre check ; pyright alteza ; pytype alteza`. Pytype is pretty slow, so feel free to omit it.

### Linting

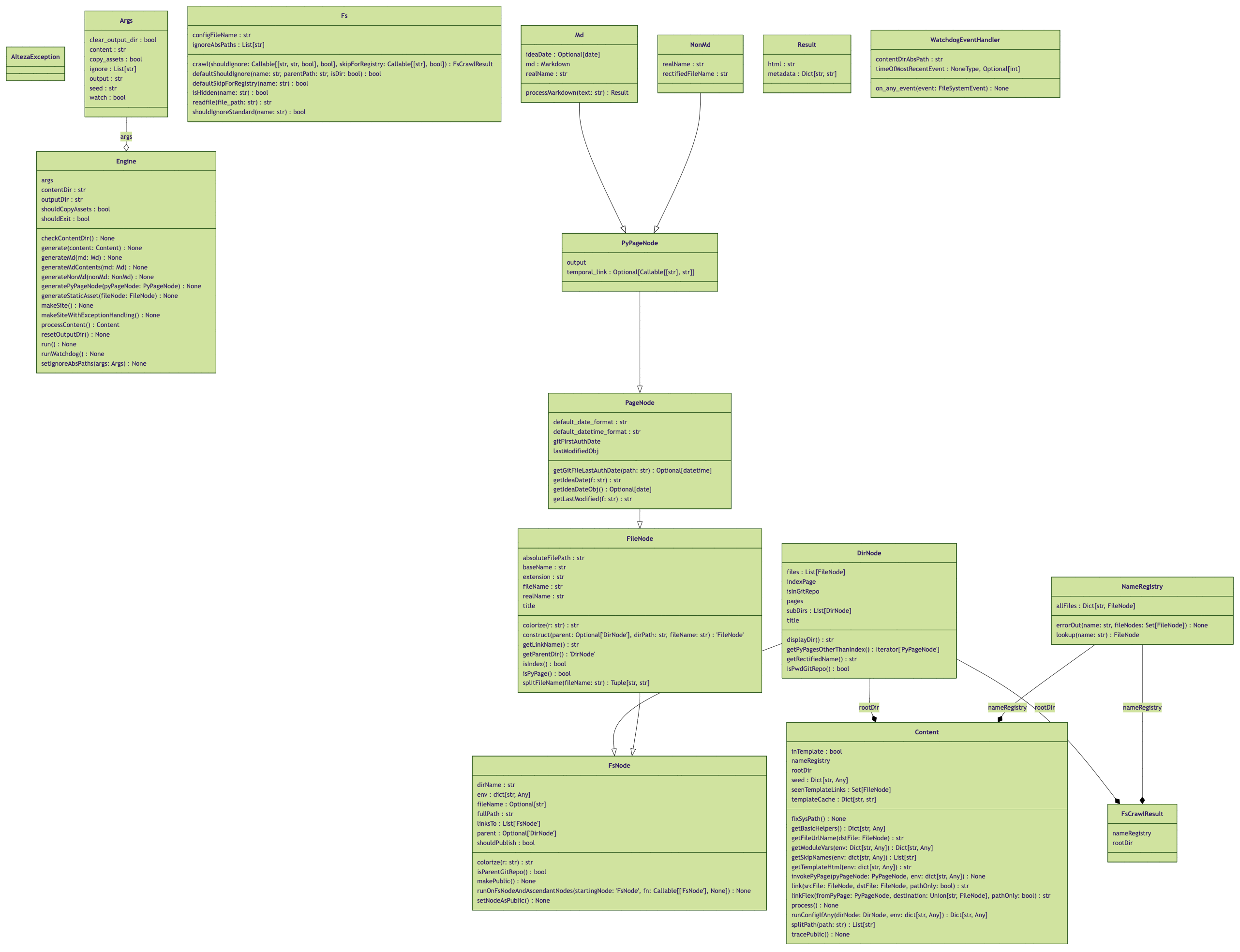

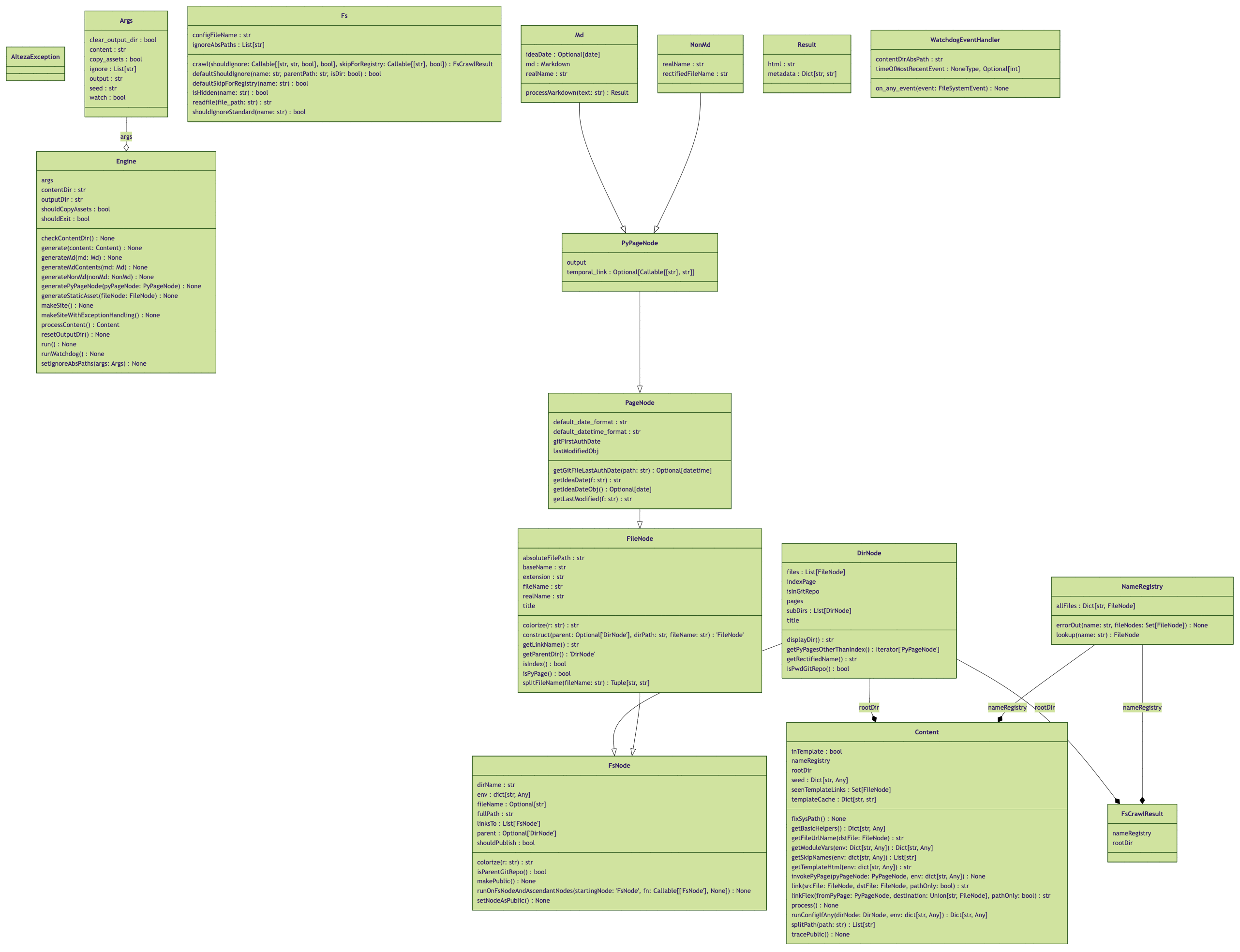

Linting policy is very strict. [Pylint](https://pylint.pycqa.org/en/latest/index.html) must issue a perfect 10/10 score, otherwise the Pylint CI check will fail. On a side note, you can see a UML diagram of the Alteza code if you click on any one of the completed workflow runs for the [Pylint CI check](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza/actions/workflows/pylint.yml).

To test whether lints are passing, simply run:

```

pylint -j 0 alteza

```

To run it along with all the type checks (excluding `pytype`), just run: `mypy alteza ; pyre check ; pyright alteza ; pyflakes alteza ; pylint -j 0 alteza`. I run this often.

Of course, when it makes sense, lints should be suppressed next to the relevant line, in code. Also, unlike typical Python code, the naming convention generally-followed in this codebase is `camelCase`. Pylint checks for names have mostly been disabled.

Here's the Pylint-generated UML diagram of Alteza's code (that's current as of v0.9.0):

### Dependencies

To install dependencies for development, run:

```sh

python3 -m pip install -r requirements.txt

python3 -m pip install -r requirements-dev.txt

```

To use a virtual environment (after creating one with `python3 -m venv venv`):

```sh

source venv/bin/activate

# ... install requirements ...

# ... do some development ...

deactive # end the venv

```

---

### License

This project is licensed under the AGPL v3, but I'm reserving the right to re-license it under a license with fewer restrictions, e.g. the Apache License 2.0, and any PRs constitute consent to re-license as such.

Raw data

{

"_id": null,

"home_page": "https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza",

"name": "alteza",

"maintainer": null,

"docs_url": null,

"requires_python": ">=3.10",

"maintainer_email": null,

"keywords": "static site generator, static sites, ssg",

"author": "Arjun G. Menon",

"author_email": "contact@arjungmenon.com",

"download_url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/packages/ca/95/1a66b9e79c9e40974678252e0617c41253493a4feb7bcfbef9286fbf98a1/alteza-0.9.1.tar.gz",

"platform": null,

"description": "# Alteza [](https://pypi.org/project/alteza/) [](https://github.com/arjun-menon/appletree/actions/workflows/type-checks.yml/) [](https://github.com/arjun-menon/appletree/actions/workflows/test-run.yml/)\n\nAlteza is a static site generator<sup>[<img height=\"10\" width=\"10\" src=\"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/8/80/Wikipedia-logo-v2.svg/103px-Wikipedia-logo-v2.svg.png\" />](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Static_site_generator)</sup> driven by [PyPage](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage).\nExamples of other static site generators can be [found here](https://github.com/collections/static-site-generators).\n\nAlteza can be thought of as a simpler and more flexible alternative to static site generators like [Jekyll](https://jekyllrb.com/), [Hugo](https://gohugo.io/), [Zola](https://www.getzola.org/), [Nextra](https://nextra.site/), etc.\n\nThe differentiator with Alteza is that the site author (if familiar with Python) will have a lot more \nfine-grained control over the output, than what (as far as I'm aware) any of the existing options offer.\n\nThe learning curve is also shorter with Alteza. I've tried to follow [xmonad](https://xmonad.org/)'s philosophy\nof keeping things small and simple. Alteza doesn't try to do a lot of things; instead it simply offers the core crucial\nfunctionality that is common to most static site generators.\n\nAlteza also imposes very little _required_ structure or a particular \"way of doing things\" on your website (other than\nrequiring unique names). You retain the freedom to organize your website as you wish. The name _Alteza_ comes from\na word that may be translated to [illustriousness](https://m.interglot.com/en/es/illustriousness) in Espa\u00f1ol.\n\nA key design aspect of Alteza is writing little scripts and executing such code to generate your website. Your static\nsite can contain arbitrary Python that is executed at the time of site generation. [PyPage](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage),\nin particular, makes it seamless to include actual Python code inside page templates. (This of course means that you\nmust run Alteza with trusted code, or in an isolated container. For example, in a [GitHub action\u2013see instructions below](#github-action).)\n\n## User Guide\n\n1. The directory structure is generally mirrored in the generated site.\n\n2. By default, nothing is copied/published to the generated site.\n * A file must explicitly indicate using a `public: true` variable/field that it is to be published.\n * Therefore, directories with no public files do not exist in the generated site.\n * Files _reachable_ from marked-as-public files will also be publicly accessible.\n * Here, reachability is discovered when a provided `link` function is used to link to other files.\n * All files starting with a `.` are ignored.\n\n3. All file and directory names, except for index page files, _at all depth levels_ must be unique. This is to simplify use of the `link(name)` function. With unique file and directory names, one can simply link to a file or directory with just its name, without needing to disambiguate a non-unique name with its path. Note: Directories can only be linked to if the directory contains an index page.\n\n4. There are two kinds of files: **static asset** files, and **PyPage** (i.e. dynamic *template/layout* or *content*) files. PyPage files get processed by the [PyPage](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage) template engine.\n\n5. **Static asset** files are **_not_** read by Alteza. They are _selectively_ either **symlink**ed or **copied** to the output directory (you can choose which, with a command-line argument). Here, _selectively_ means that they are exposed in the output directory _only if they are linked to_ from a PyPage file using a special Alteza-provided `link(name)` function.\n\n6. PyPage files are determined based on their file name extension. They are of two kinds:\n 1. **Markdown** files (i.e. files ending with `.md`).\n 2. Any file with a `.py` before its actual extension (_i.e. any file with a `.py` before the last `.` in its file name_). These are **Non-Markdown Pypage files**.\n\n7. There is an inherited \"environment\"/`env` (this is just a collection of Python variables) that is injected into the lexical scope of every PyPage file, before it is processed/executed by PyPage. This `env` is a little different for each PyPage invocation--a copy of the inherited is `env` is created for each PyPage file. More on `env` in a later point below.\n\n8. **Non-Markdown Pypage files** are simply processed with PyPage as-is (and there is no template application step for non-Markdown PyPage files). The `.py` part is removed from their name, and the output/result is copied to the generated site.\n\n9. **Markdown** files:\n 1. Markdown files are first processed with PyPage, with a copy of the inherited `env`.\n\n 2. After this, the Markdown file is converted to HTML using the [Python-Markdown](https://python-markdown.github.io/reference/) library.\n\n 3. Third, they have their \"front matter\" (if any) extracted using the Python-Markdown's library [Meta-Data](https://python-markdown.github.io/extensions/meta_data/) extension/feature.\n 1. The first line with a `---` in the Markdown file ends the front matter section.\n 2. The front matter is processed by Alteza as YAML using the [PyYAML](https://pyyaml.org/wiki/PyYAML).\n\n 4. The fields from the YAML front matter the fields are injected into the `env`/environment.\n\n 5. The HTML is injected into a `content` variable in `env`, and this `env` is passed to a `layout` **template** specified _in configuration_, for a second round of processing by PyPage. (Note: PyPage here is invoked on the template.)\n\n 1. Templates are HTML files processed by PyPage. The PyPage-processed Markdown HTML output is passed to the template/layout as the `content` variable. The template itself is then executed by PyPage.\n\n 2. The template/layout should use this `content` value via PyPage (with `{{ content }}`) in order to inject the `content` into itself.\n\n 3. The template is specified using a `layout` or `layoutRaw` variable declared in a `__config__.py` file. (More on configuration files in a later point below.)\n\n 4. A `layout` variable's value must be the name of a template.\n\n 1. For example, you can write `layout: ordinary-page` in the YAML front matter of a Markdown file.\n\n 2. Or, alternatively, you can also write `layout = \"ordinary_page\"` in a `__config__.py` file. If a `layout` variable is defined like this in a `__config__.py` all adjacent and descendant files will inherit this `layout` value.\n\n 1. This can be used as a way of defining a _**default**_ layout/template.\n\n 2. Of course, the default can be overridden in a Markdown file by specifying a layout name in the YAML front matter, or with a new default in a descendant `__config__.py`.\n\n 3. Lastly, alternatively, a `layoutRaw` can also be defined whose value must be the entire contents of a template PyPage-HTML file. A convenience function `readfile` is provided for this. For example, you can write something like `layout = readfile('some_layout.html')` in a config file. A `layoutRaw`, if specified, takes precedence over `layout`. Using this `layoutRaw` approach is not recommended.\n\n 5. Layouts/templates may be overridden in descendant `__config__.py` files. Or, may be overridden in the Markdown file _**itself**_ using YAML front matter (by specifying a `layout: ...`), or even in a PyPage multiline code tag (not an inline code tag) inside a PyPage file (with a `layout = ...`).\n\n 6. Markdown files result in **_a directory_** with the base name (_i.e. without the `.md` extension_), with an `index.html` file containing the Markdown's output.\n\n10. The **Environment** (`env`) and **Configuration** (`__config__.py`, etc.):\n\n 1. _Note:_ Python code in both `.md` and other `.py.*` files are run using Python's built-in [`exec`](https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#exec) (and [`eval`](https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#eval)) functions, and when they're run, we passed in a dictionary for their `globals` argument. We call that dict the **environment**, or `env`.\n\n 2. Configuration is done through file(s) called `__config__.py`.\n\n 1. First, we recursively go through all directories top-down.\n\n 2. At each directory (descending downward), we execute an `__config__.py` file, if one is present. After execution, we absorb any variables in it that do not start with a `_` into the `env` dict.\n\n 3. The deepest `.md`/`.py.*` files get executed first. After it executes, we check if a `env` contains a field `public` that is set as `True`. If it does, we mark that file for publication. Other than recording the value of `public` after each dynamic file is executed, any modification to `env` made by a dynamic file are discarded (and not absorbed, unlike with `__config__.py`).\n * I would not recommend using `__config__.py` to set `public` as `True`, as that would make the entire directory and all its descendants public (unless that behavior is exactly what is desired). Reachability with `link` (described below) is, in my opinion, a better way to make _only reachable_ content publicly exposed.\n\n11. The **Name Registry** and the **`link`** function.\n\n 1. The name of every file in the input content is stored in a \"name registry\" of sorts that's used by `link`.\n\n 1. Currently, names, without their file extension, have to be unique across input content. This might change in the future.\n\n 2. The Name Registry will error out if it encounters any non-unique names. (I understand this is a significant limitation, so I _might_ support making this opt-out behavior with a `--nonunique` flag in the future.)\n\n 2. Any non-dynamic content file that has been `link`-ed to is marked for publication (i.e. copying or symlinking).\n\n 3. A Python function named `link` is injected into the top level `env`.\n\n 1. This function can be used to get relative links to any other file. `link` will automatically determine and return the relative path to a file.\n * For example, one can do `<a href=\"{{link('some-other-blog-post')}}\">`, and the generated site will have a relative link to it (i.e. to its directory if a Markdown file, and to the file itself otherwise).\n\n 2. Reachability of files is determined using this function, and unreachable files will be treated as non-public (and thus not exist in the generated site).\n\n 3. This function can be called both with a string identifying a file name, or with a reference to the file object itself. `link` will check the type of the argument passed to it, and appropriately handle each type.\n\n 4. This `link` function can also be called with string arguments using wiki-style links in Markdown files. For example, a `[[Happy Cat]]` in a Markdown file is the equivalent of writing `[Happy Cat]({{link('Happy Cat')}})`, or of writing `<a href=\"{{link('Happy Cat')}}\">Happy Cat</a>`.\n\n 4. A file name's extension must be omitted while using `link` (including the `.py*` for any file with `.py` before its extension).\n * i.e., e.g. one must write `link('magic-turtle')` for the file `magic-turtle.md`, and `link('pygments-styles')` for the file `pygments-styles.py.css`.\n * Directories containing index files should just be referred to by the directory name. For example, the index page `about-me/hobbies/index.md` (or `about-me/hobbies/index.py.html`) should just be linked to with a `link('hobbies')`.\n\n12. #### Expected (and Optional) Special Variables/Functions\n\n Certain fields, with certain names, hold special meaning, and are called/used by Alteza. One such variable is `layout` (and `layoutRaw`), which points to the layout/template to be used to render the page (as explained in earlier points above). It can be overriden by descendant directories or pages.\n\n #### Built-in Functions and Fields\n <table>\n<tr>\n<th>Built-in</th>\n<th>Description</th>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td><code>link</code></td>\n<td>\n\nThe `link` function takes **a name** or an object, and returns _a **relative** link_ to it. If a name is provided, it looks for that name in the NameRegistry (and throws an exception if the name wasn't found).\n\nThe `link` function has the side effect of making the linked-to page publicly accessible, if the page that is creating the link is reachable from another publicly-accessible page. The root `/` index page is always public.\n\n_Note:_ for Markdown pages, an extra `../` is added at the beginning of the returned path to accommodate the fact that Markdown pages get turned into directories with the page rendered into an `index.html` inside the directory.\n\nAvailability:\n<table>\n<tr>\n<td>Page</td>\n<td>Template</td>\n<td>Config</td>\n<td>Index</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td align=\"center\">\u2705</td><td align=\"center\">\u2705</td><td align=\"center\">\u274c</td><td align=\"center\">\u2705</td>\n</tr>\n</table>\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td><code>path</code></td>\n<td>\n\nThe `path` function is similar to the `path` function above, except that:\n* it _**does not**_ have the side effect of impacting the reachability graph, and making the linked-to page publicly accessible, and\n* it also does not add an extra `../` at the beginning of the returned path for Markdown pages.\n\nThis function is good for use inside templates, to reference parent/ancestor templates for injection. For example, writing something like `{{ inject(path('skeleton')) }}`.\n\nAvailable everywhere.\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td><code>dir</code></td>\n<td>\n\nThe `dir` variables points to a `DirNode` object representing the directory that the relevant file is in.\n\nThis object has a fields like `dir.pages`, which is a list of all the pages (a list of `PageNode` objects) representing all the pages in that directory. Pages means Markdown files and HTML files. Some of the fields in `dir` are:\n\n 1. `dir.subDirs`: List of `FileNode` objects of files in this directory.\n 2. `dir.files`: List of `FileNode` objects of files in this directory.\n 3. `dir.pages`: List of `PageNode` objects of Markdown files, non-Markdown PyPage files, and HTML files.\n 4. `dir.indexPage`: A `PageNode` object of the index page, i.e. a `index.md` or a `index.html` file. If there is no index page, this is `None`.\n 5. `dir.title`: A string `title` object of the index page, only if the index page specifies a title. If there is no index page or no title specified by it, this is `None`.\n\nIn templates, the `dir` points to the directory that the file being processed is in.\n\nAvailable everywhere.\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td>Title</td>\n<td>The title is accessed with <code>page.title</code>. It is picked up either from PyPage code in the page or a <code>title</code> YAML field in the file. If `title` is not defined by the page, then <code>page.realName</code> of the file is used, which is the adjusted name of the file without its extension and idea date prefix (if present) removed. The title isn't <em>properly</em> available to Python inside the page itself, or from <code>__config__.py</code>, since the page has not been processed when these are executed. If <code>page.title</code> is accessed from these (the page or config), or if a <code>title</code> was never defined in the page, then the <code>.realName</code> of the file would be returned.\n\nNote: the title can directly be accessed as `title` (without `pageObj.title`) in the template (and [inherited](https://github.com/arjun-menon/pypage?tab=readme-ov-file#inheritance-with-inject-and-exists) templates) for the page, since all environment variables from the page are passed on to the template, during template processing.\n\nAvailability:\n<table>\n<tr>\n<td>Page</td>\n<td>Template</td>\n<td>Config</td>\n<td>Index</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td align=\"center\">\u274c</td><td align=\"center\">\u2705</td><td align=\"center\">\u274c</td><td align=\"center\">\u2705</td>\n</tr>\n</table>\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td>YAML fields & other vars</td>\n<td>\n\nYAML fields (and other variables defined in PyPage code) of a page are:\n* Available directly to template(s) that the page uses/invokes.\n* Stored in `pageObj.env`, for future access. The index page, for example, can use `page.env` to access these fields & variables.\n* Stored _**as attributes**_ in the `PyPageNode` page object, as long as the `env` var does not conflict with an existing attribute of `PyPageNode`.\n * This enables referring to a field or variable with just `page.fieldName` (instead of having to write `page.env[fieldName]`, which is also valid).\n<br />\n\nAvailability (same as `title`):\n<table>\n<tr>\n<td>Page</td>\n<td>Template</td>\n<td>Config</td>\n<td>Index</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td align=\"center\">\u274c</td><td align=\"center\">\u2705</td><td align=\"center\">\u274c</td><td align=\"center\">\u2705</td>\n</tr>\n</table>\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td>Last Modified Date & Time</td>\n<td>\n\n_This is only available on `PageNode` objects._\n\nThe last modified date & time for a given file is taken from:\n\n a. The date & time of _the last commit that modified that file_, in git history, if the file is inside a git repo.\n\n b. The last modified date & time as provided by the file system. \n\nThere's a `getLastModifiedObj()` function which returns a Python `datetime` object. There's also a `getLastModified(f: str = default_datetime_format)` functon which returns a `str` with the date & time formatted.\n\nThe `default_datetime_format` is `%Y %b %-d at %-H:%M %p`.\n\n_Note:_ This function calls spawns a `git` process, so is a tiny bit slow.\n\nAvailable everywhere.\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td>Idea Date</td>\n<td>\n\n_This is only available on `PageNode` objects._\n\nThe \"idea date\" for a given file is either:\n\n a. For a Markdown file, a date prefix before the markdown file's name, in the form `YYYY-MM-DD`.\n\n b. If not a Markdown file or there's no date prefix, and _the file is in a git repo_, then the idea date is the date of the first commit that introduced the file into git history. (Note: this breaks if the file was renamed or moved.) \n\n c. If there is neither a date prefix and the file is not in a git repo, there is no idea date for that file (i.e. it's `None` or `\"\"`).\n\nThere's a `getIdeaDateObj()` function which returns a Python `date` object (or `None` if there's no idea). There's also a `getIdeaDate(f: str = default_date_format)` functon which returns a `str` with the date & time formatted or `\"\"` if there's no idea date.\n\nThe `default_date_format` is `%Y %b %-d`.\n\n_Note:_ This function calls spawns a `git` process, if it's not a Markdown file or if there is no date prefix in the Markdown file's name.\n\nAvailable everywhere.\n\n</td>\n</tr>\n<tr>\n<td><code>readfile</code></td>\n<td>This is just a simple built-in function that reads the contents of a file (assuming <code>utf-8</code> encoding) into a string, and returns it.\nAvailable everywhere.\n</td>\n</tr>\n\n<tr>\n<td><code>sh</code></td>\n<td>This exposes the entire <code>sh</code> library. The current working directory (CWD) would be wherever the file being executed is located (regardless of whether the file is a regular page or index page or <code>__config__.py</code> or template). If the file is a template, the CWD would be that of the page being processed.\n\nSee `sh`'s documentation here: https://sh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/\n\nAvailable everywhere.\n</td>\n</tr>\n\n<tr>\n<td><code>skip</code></td>\n<td>This environment variable, if specified, is a list of names of files or directories to be skipped. (It must be of type <code>List[str]</code>, if defined.)\n</td>\n</tr>\n\n</table>\n\n## GitHub Action, Installation & Command-Line Usage\n\n### GitHub Action\n\nAlteza is available as a GitHub action, for use with GitHub Pages. This is the simplest way to use Alteza, if you intend to use it with GitHub Pages. Using the GitHub action will avoid needing to install or configure Alteza. You can easily create & deply an Alteza website onto GitHub Pages using this action.\n\nTo use the GitHub action, create a workflow file called something like `.github/workflows/alteza.yml`, and paste the following in it:\n```yml\nname: Alteza\n\non:\n workflow_dispatch:\n push:\n branches: [ \"main\" ]\n\njobs:\n build:\n name: Build Website\n runs-on: ubuntu-latest\n\n permissions:\n contents: read\n pages: write\n id-token: write\n\n environment:\n name: github-pages\n url: ${{ steps.generate.outputs.page_url }}\n\n steps:\n - name: Generate Alteza Website\n id: generate\n uses: arjun-menon/alteza@v0.9.1\n with:\n path: .\n```\nThe last parameter `path` should specify which directory in your GitHub repo should be rendered into a website. Also, note: make sure to set the `branches` for `workflow_dispatch` correctly (to your branch) so that this action is triggered on each push.\n\nFor an example of this GitHub workflow above in action, see [alteza-test](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza-test) ([yaml](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza-test/blob/main/.github/workflows/alteza.yml), [runs](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza-test/actions/workflows/alteza.yml)).\n\n### Installation\n\nYou can [install](https://docs.python.org/3/installing/) Alteza easily with [pip](https://pip.pypa.io/en/stable/):\n\n```\npip install alteza\n```\nTry running `alteza -h` to see the command-line options available.\n\n### Running\n\nIf you've installed Alteza with pip, you can just run `alteza`, e.g.:\n```sh\nalteza -h\n```\nIf you're working on Alteza itself, then run the `alteza` module itself, from the project directory directly, e.g. `python3 -m alteza -h`.\n\n### Command-line Arguments\nThe `-h` argument above will print the list of available arguments:\n```\nusage: __main__.py --content CONTENT --output OUTPUT [--clear_output_dir] [--copy_assets] [--seed SEED] [--watch]\n [--ignore [IGNORE ...]] [-h]\n\noptions:\n --content CONTENT (str, required) Directory to read the input content from.\n --output OUTPUT (str, required) Directory to write the generated site to.\n --clear_output_dir (bool, default=False) Delete the output directory, if it already exists.\n --copy_assets (bool, default=False) Copy static assets instead of symlinking to them.\n --seed SEED (str, default={}) Seed JSON data to add to the initial root env.\n --watch (bool, default=False) Watch for content changes, and rebuild.\n --ignore [IGNORE ...]\n (List[str], default=[]) Paths to completely ignore.\n -h, --help show this help message and exit\n```\nAs might be obvious above, you set the `--content` field to your content directory.\n\nThe output directory for the generated site is specified with `--output`. You can have Alteza automatically delete it entirely before being written to (including in `--watch` mode) by setting the `--clear_output_dir` flag.\n\nNormally, Alteza performs a single build and exits. With the `--watch` flag, Alteza monitors the file system for changes, and rebuilds the site automatically. \n\nThe `--ignore` flag is a list of _paths_ to files or directories to ignore. This is useful for ignoring directories like `.gitignore`, or other non-pertinent files and directories.\n\nNormal Alteza behavior for static assets is to create symlinks from your generate site to static files in your content directory. You can turn off this behavior with `--copy_assets`.\n\nThe `--seed` flag is a JSON string representing seed data for PyPage processing. This seed is injected into every PyPage document. The seed _is not global_, and so cannot be modified between files; it is copied into each PyPage execution environment.\n\nTo test against `test_content` (and generate output to `test_output`), run it like this:\n```sh\npython -m alteza --content test_content --output test_output --clear_output_dir\n```\n\n## Development & Testing\n\nFeel free to send me PRs for this project.\n\n### Code Style\n\nI'm using `black`. To re-format the code, just run: `black alteza`.\nFwiw, I've configured my IDE (_PyCharm_) to always auto-format with `black`.\n\n### Type Checking\n\nTo ensure better code quality, Alteza is type-checked with five different type checking systems: [Mypy](https://mypy-lang.org/), Meta's [Pyre](https://pyre-check.org/), Microsoft's [Pyright](https://github.com/microsoft/pyright), Google's [Pytype](https://github.com/google/pytype), and [Pyflakes](https://pypi.org/project/pyflakes/); as well as linted with [Pylint](https://pylint.pycqa.org/en/latest/index.html).\n\nTo run some type checks:\n```sh\nmypy alteza # should have zero errors\npyflakes alteza # should have zero errors\npyre check # should have zero errors as well\npyright alteza # should have zero errors also\npytype alteza # should have zero errors too\n```\nOr, all at once with: `mypy alteza ; pyflakes alteza ; pyre check ; pyright alteza ; pytype alteza`. Pytype is pretty slow, so feel free to omit it.\n\n### Linting\nLinting policy is very strict. [Pylint](https://pylint.pycqa.org/en/latest/index.html) must issue a perfect 10/10 score, otherwise the Pylint CI check will fail. On a side note, you can see a UML diagram of the Alteza code if you click on any one of the completed workflow runs for the [Pylint CI check](https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza/actions/workflows/pylint.yml).\n\nTo test whether lints are passing, simply run:\n```\npylint -j 0 alteza\n```\nTo run it along with all the type checks (excluding `pytype`), just run: `mypy alteza ; pyre check ; pyright alteza ; pyflakes alteza ; pylint -j 0 alteza`. I run this often.\n\nOf course, when it makes sense, lints should be suppressed next to the relevant line, in code. Also, unlike typical Python code, the naming convention generally-followed in this codebase is `camelCase`. Pylint checks for names have mostly been disabled.\n\nHere's the Pylint-generated UML diagram of Alteza's code (that's current as of v0.9.0):\n\n\n\n### Dependencies\n\nTo install dependencies for development, run:\n```sh\npython3 -m pip install -r requirements.txt\npython3 -m pip install -r requirements-dev.txt\n```\n\nTo use a virtual environment (after creating one with `python3 -m venv venv`):\n```sh\nsource venv/bin/activate\n# ... install requirements ...\n# ... do some development ...\ndeactive # end the venv\n```\n\n---\n\n### License\nThis project is licensed under the AGPL v3, but I'm reserving the right to re-license it under a license with fewer restrictions, e.g. the Apache License 2.0, and any PRs constitute consent to re-license as such.\n",

"bugtrack_url": null,

"license": "AGPL-3.0-or-later",

"summary": "Super-flexible Static Site Generator",

"version": "0.9.1",

"project_urls": {

"Download": "https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza/archive/v0.9.1.tar.gz",

"Homepage": "https://github.com/arjun-menon/alteza"

},

"split_keywords": [

"static site generator",

" static sites",

" ssg"

],

"urls": [

{

"comment_text": "",

"digests": {

"blake2b_256": "5d3a543e5254b40424e9a8fc5aec4f4f540bca46d81d636396a488380c591b32",

"md5": "c57dcd065a155cbb87c4d9ff1d2499b1",

"sha256": "32b1782dc528f97d809120a2e53899c5407c5a4c1dcb4ec772cf2798c3788a1b"

},

"downloads": -1,

"filename": "alteza-0.9.1-py3-none-any.whl",

"has_sig": false,

"md5_digest": "c57dcd065a155cbb87c4d9ff1d2499b1",

"packagetype": "bdist_wheel",

"python_version": "py3",

"requires_python": ">=3.10",

"size": 35003,

"upload_time": "2024-11-26T12:34:06",

"upload_time_iso_8601": "2024-11-26T12:34:06.614407Z",

"url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/packages/5d/3a/543e5254b40424e9a8fc5aec4f4f540bca46d81d636396a488380c591b32/alteza-0.9.1-py3-none-any.whl",

"yanked": false,

"yanked_reason": null

},

{

"comment_text": "",

"digests": {

"blake2b_256": "ca951a66b9e79c9e40974678252e0617c41253493a4feb7bcfbef9286fbf98a1",

"md5": "f118dbed80c2d11cc9a93b5cae7d4ae1",

"sha256": "b016e893aad694328002b2d841574e5ae9b72fdd48392d658099bde4a3fa75ad"

},

"downloads": -1,

"filename": "alteza-0.9.1.tar.gz",

"has_sig": false,

"md5_digest": "f118dbed80c2d11cc9a93b5cae7d4ae1",

"packagetype": "sdist",

"python_version": "source",

"requires_python": ">=3.10",

"size": 50326,

"upload_time": "2024-11-26T12:34:08",

"upload_time_iso_8601": "2024-11-26T12:34:08.499080Z",

"url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/packages/ca/95/1a66b9e79c9e40974678252e0617c41253493a4feb7bcfbef9286fbf98a1/alteza-0.9.1.tar.gz",

"yanked": false,

"yanked_reason": null

}

],

"upload_time": "2024-11-26 12:34:08",

"github": true,

"gitlab": false,

"bitbucket": false,

"codeberg": false,

"github_user": "arjun-menon",

"github_project": "alteza",

"travis_ci": false,

"coveralls": false,

"github_actions": true,

"requirements": [

{

"name": "colored",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"2.2.4"

]

]

},

{

"name": "docstring-parser",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"0.15"

]

]

},

{

"name": "markdown",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"3.6"

]

]

},

{

"name": "mdx-breakless-lists",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"1.0.1"

]

]

},

{

"name": "mdx-truly-sane-lists",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"1.3"

]

]

},

{

"name": "mypy-extensions",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"1.0.0"

]

]

},

{

"name": "packaging",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"24.1"

]

]

},

{

"name": "pygments",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"2.17.2"

]

]

},

{

"name": "pypage",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"2.1.0"

]

]

},

{

"name": "pyyaml",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"6.0.1"

]

]

},

{

"name": "sh",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"2.0.7"

]

]

},

{

"name": "typed-argument-parser",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"1.10.1"

]

]

},

{

"name": "typing-extensions",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"4.9.0"

]

]

},

{

"name": "typing-inspect",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"0.9.0"

]

]

},

{

"name": "watchdog",

"specs": [

[

"==",

"4.0.1"

]

]

}

],

"lcname": "alteza"

}