# stack_data

[](https://github.com/alexmojaki/stack_data/actions/workflows/pytest.yml) [](https://coveralls.io/github/alexmojaki/stack_data?branch=master) [](https://pypi.python.org/pypi/stack_data)

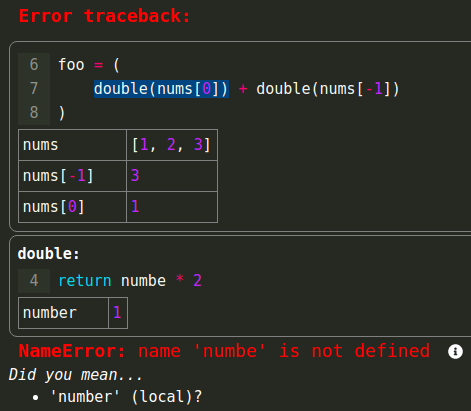

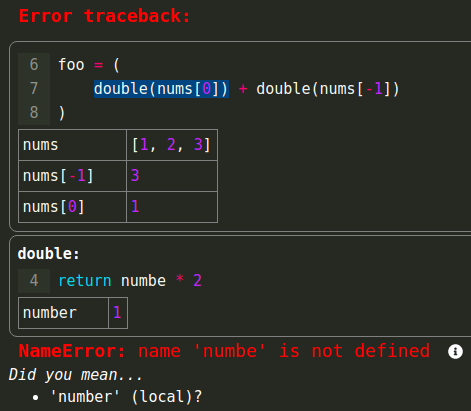

This is a library that extracts data from stack frames and tracebacks, particularly to display more useful tracebacks than the default. It powers the tracebacks in IPython and [futurecoder](https://futurecoder.io/):

You can install it from PyPI:

pip install stack_data

## Basic usage

Here's some code we'd like to inspect:

```python

def foo():

result = []

for i in range(5):

row = []

result.append(row)

print_stack()

for j in range(5):

row.append(i * j)

return result

```

Note that `foo` calls a function `print_stack()`. In reality we can imagine that an exception was raised at this line, or a debugger stopped there, but this is easy to play with directly. Here's a basic implementation:

```python

import inspect

import stack_data

def print_stack():

frame = inspect.currentframe().f_back

frame_info = stack_data.FrameInfo(frame)

print(f"{frame_info.code.co_name} at line {frame_info.lineno}")

print("-----------")

for line in frame_info.lines:

print(f"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render()}")

```

(Beware that this has a major bug - it doesn't account for line gaps, which we'll learn about later)

The output of one call to `print_stack()` looks like:

```

foo at line 9

-----------

6 | for i in range(5):

7 | row = []

8 | result.append(row)

--> 9 | print_stack()

10 | for j in range(5):

```

The code for `print_stack()` is fairly self-explanatory. If you want to learn more details about a particular class or method I suggest looking through some docstrings. `FrameInfo` is a class that accepts either a frame or a traceback object and provides a bunch of nice attributes and properties (which are cached so you don't need to worry about performance). In particular `frame_info.lines` is a list of `Line` objects. `line.render()` returns the source code of that line suitable for display. Without any arguments it simply strips any common leading indentation. Later on we'll see a more powerful use for it.

You can see that `frame_info.lines` includes some lines of surrounding context. By default it includes 3 pieces of context before the main line and 1 piece after. We can configure the amount of context by passing options:

```python

options = stack_data.Options(before=1, after=0)

frame_info = stack_data.FrameInfo(frame, options)

```

Then the output looks like:

```

foo at line 9

-----------

8 | result.append(row)

--> 9 | print_stack()

```

Note that these parameters are not the number of *lines* before and after to include, but the number of *pieces*. A piece is a range of one or more lines in a file that should logically be grouped together. A piece contains either a single simple statement or a part of a compound statement (loops, if, try/except, etc) that doesn't contain any other statements. Most pieces are a single line, but a multi-line statement or `if` condition is a single piece. In the example above, all pieces are one line, because nothing is spread across multiple lines. If we change our code to include some multiline bits:

```python

def foo():

result = []

for i in range(5):

row = []

result.append(

row

)

print_stack()

for j in range(

5

):

row.append(i * j)

return result

```

and then run the original code with the default options, then the output is:

```

foo at line 11

-----------

6 | for i in range(5):

7 | row = []

8 | result.append(

9 | row

10 | )

--> 11 | print_stack()

12 | for j in range(

13 | 5

14 | ):

```

Now lines 8-10 and lines 12-14 are each a single piece. Note that the output is essentially the same as the original in terms of the amount of code. The division of files into pieces means that the edge of the context is intuitive and doesn't crop out parts of statements or expressions. For example, if context was measured in lines instead of pieces, the last line of the above would be `for j in range(` which is much less useful.

However, if a piece is very long, including all of it could be cumbersome. For this, `Options` has a parameter `max_lines_per_piece`, which is 6 by default. Suppose we have a piece in our code that's longer than that:

```python

row = [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

]

```

`frame_info.lines` will truncate this piece so that instead of 7 `Line` objects it will produce 5 `Line` objects and one `LINE_GAP` in the middle, making 6 objects in total for the piece. Our code doesn't currently handle gaps, so it will raise an exception. We can modify it like so:

```python

for line in frame_info.lines:

if line is stack_data.LINE_GAP:

print(" (...)")

else:

print(f"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render()}")

```

Now the output looks like:

```

foo at line 15

-----------

6 | for i in range(5):

7 | row = [

8 | 1,

9 | 2,

(...)

12 | 5,

13 | ]

14 | result.append(row)

--> 15 | print_stack()

16 | for j in range(5):

```

Alternatively, you can flip the condition around and check `if isinstance(line, stack_data.Line):`. Either way, you should always check for line gaps, or your code may appear to work at first but fail when it encounters a long piece.

Note that the executing piece, i.e. the piece containing the current line being executed (line 15 in this case) is never truncated, no matter how long it is.

The lines of context never stray outside `frame_info.scope`, which is the innermost function or class definition containing the current line. For example, this is the output for a short function which has neither 3 lines before nor 1 line after the current line:

```

bar at line 6

-----------

4 | def bar():

5 | foo()

--> 6 | print_stack()

```

Sometimes it's nice to ensure that the function signature is always showing. This can be done with `Options(include_signature=True)`. The result looks like this:

```

foo at line 14

-----------

9 | def foo():

(...)

11 | for i in range(5):

12 | row = []

13 | result.append(row)

--> 14 | print_stack()

15 | for j in range(5):

```

To avoid wasting space, pieces never start or end with a blank line, and blank lines between pieces are excluded. So if our code looks like this:

```python

for i in range(5):

row = []

result.append(row)

print_stack()

for j in range(5):

```

The output doesn't change much, except you can see jumps in the line numbers:

```

11 | for i in range(5):

12 | row = []

14 | result.append(row)

--> 15 | print_stack()

17 | for j in range(5):

```

## Variables

You can also inspect variables and other expressions in a frame, e.g:

```python

for var in frame_info.variables:

print(f"{var.name} = {repr(var.value)}")

```

which may output:

```python

result = [[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [0, 2, 4, 6, 8], [0, 3, 6, 9, 12], []]

i = 4

row = []

j = 4

```

`frame_info.variables` returns a list of `Variable` objects, which have attributes `name`, `value`, and `nodes`, which is a list of all AST representing that expression.

A `Variable` may refer to an expression other than a simple variable name. It can be any expression evaluated by the library [`pure_eval`](https://github.com/alexmojaki/pure_eval) which it deems 'interesting' (see those docs for more info). This includes expressions like `foo.bar` or `foo[bar]`. In these cases `name` is the source code of that expression. `pure_eval` ensures that it only evaluates expressions that won't have any side effects, e.g. where `foo.bar` is a normal attribute rather than a descriptor such as a property.

`frame_info.variables` is a list of all the interesting expressions found in `frame_info.scope`, e.g. the current function, which may include expressions not visible in `frame_info.lines`. You can restrict the list by using `frame_info.variables_in_lines` or even `frame_info.variables_in_executing_piece`. For more control you can use `frame_info.variables_by_lineno`. See the docstrings for more information.

## Rendering lines with ranges and markers

Sometimes you may want to insert special characters into the text for display purposes, e.g. HTML or ANSI color codes. `stack_data` provides a few tools to make this easier.

Let's say we have a `Line` object where `line.text` (the original raw source code of that line) is `"foo = bar"`, so `line.text[6:9]` is `"bar"`, and we want to emphasise that part by inserting HTML at positions 6 and 9 in the text. Here's how we can do that directly:

```python

markers = [

stack_data.MarkerInLine(position=6, is_start=True, string="<b>"),

stack_data.MarkerInLine(position=9, is_start=False, string="</b>"),

]

line.render(markers) # returns "foo = <b>bar</b>"

```

Here `is_start=True` indicates that the marker is the first of a pair. This helps `line.render()` sort and insert the markers correctly so you don't end up with malformed HTML like `foo<b>.<i></b>bar</i>` where tags overlap.

Since we're inserting HTML, we should actually use `line.render(markers, escape_html=True)` which will escape special HTML characters in the Python source (but not the markers) so for example `foo = bar < spam` would be rendered as `foo = <b>bar</b> < spam`.

Usually though you wouldn't create markers directly yourself. Instead you would start with one or more ranges and then convert them, like so:

```python

ranges = [

stack_data.RangeInLine(start=0, end=3, data="foo"),

stack_data.RangeInLine(start=6, end=9, data="bar"),

]

def convert_ranges(r):

if r.data == "bar":

return "<b>", "</b>"

# This results in `markers` being the same as in the above example.

markers = stack_data.markers_from_ranges(ranges, convert_ranges)

```

`RangeInLine` has a `data` attribute which can be any object. `markers_from_ranges` accepts a converter function to which it passes all the `RangeInLine` objects. If the converter function returns a pair of strings, it creates two markers from them. Otherwise it should return `None` to indicate that the range should be ignored, as with the first range containing `"foo"` in this example.

The reason this is useful is because there are built in tools to create these ranges for you. For example, if we change our `print_stack()` function to contain this:

```python

def convert_variable_ranges(r):

variable, _node = r.data

return f'<span data-value="{repr(variable.value)}">', '</span>'

markers = stack_data.markers_from_ranges(line.variable_ranges, convert_variable_ranges)

print(f"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render(markers, escape_html=True)}")

```

Then the output becomes:

```

foo at line 15

-----------

9 | def foo():

(...)

11 | for <span data-value="4">i</span> in range(5):

12 | <span data-value="[]">row</span> = []

14 | <span data-value="[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [0, 2, 4, 6, 8], [0, 3, 6, 9, 12], []]">result</span>.append(<span data-value="[]">row</span>)

--> 15 | print_stack()

17 | for <span data-value="4">j</span> in range(5):

```

`line.variable_ranges` is a list of RangeInLines for each Variable that appears at least partially in this line. The data attribute of the range is a pair `(variable, node)` where node is the particular AST node from the list `variable.nodes` that corresponds to this range.

You can also use `line.token_ranges` (e.g. if you want to do your own syntax highlighting) or `line.executing_node_ranges` if you want to highlight the currently executing node identified by the [`executing`](https://github.com/alexmojaki/executing) library. Or if you want to make your own range from an AST node, use `line.range_from_node(node, data)`. See the docstrings for more info.

### Syntax highlighting with Pygments

If you'd like pretty colored text without the work, you can let [Pygments](https://pygments.org/) do it for you. Just follow these steps:

1. `pip install pygments` separately as it's not a dependency of `stack_data`.

2. Create a pygments formatter object such as `HtmlFormatter` or `Terminal256Formatter`.

3. Pass the formatter to `Options` in the argument `pygments_formatter`.

4. Use `line.render(pygmented=True)` to get your formatted text. In this case you can't pass any markers to `render`.

If you want, you can also highlight the executing node in the frame in combination with the pygments syntax highlighting. For this you will need:

1. A pygments style - either a style class or a string that names it. See the [documentation on styles](https://pygments.org/docs/styles/) and the [styles gallery](https://blog.yjl.im/2015/08/pygments-styles-gallery.html).

2. A modification to make to the style for the executing node, which is a string such as `"bold"` or `"bg:#ffff00"` (yellow background). See the [documentation on style rules](https://pygments.org/docs/styles/#style-rules).

3. Pass these two things to `stack_data.style_with_executing_node(style, modifier)` to get a new style class.

4. Pass the new style to your formatter when you create it.

Note that this doesn't work with `TerminalFormatter` which just uses the basic ANSI colors and doesn't use the style passed to it in general.

## Getting the full stack

Currently `print_stack()` doesn't actually print the stack, it just prints one frame. Instead of `frame_info = FrameInfo(frame, options)`, let's do this:

```python

for frame_info in FrameInfo.stack_data(frame, options):

```

Now the output looks something like this:

```

<module> at line 18

-----------

14 | for j in range(5):

15 | row.append(i * j)

16 | return result

--> 18 | bar()

bar at line 5

-----------

4 | def bar():

--> 5 | foo()

foo at line 13

-----------

10 | for i in range(5):

11 | row = []

12 | result.append(row)

--> 13 | print_stack()

14 | for j in range(5):

```

However, just as `frame_info.lines` doesn't always yield `Line` objects, `FrameInfo.stack_data` doesn't always yield `FrameInfo` objects, and we must modify our code to handle that. Let's look at some different sample code:

```python

def factorial(x):

return x * factorial(x - 1)

try:

print(factorial(5))

except:

print_stack()

```

In this code we've forgotten to include a base case in our `factorial` function so it will fail with a `RecursionError` and there'll be many frames with similar information. Similar to the built in Python traceback, `stack_data` avoids showing all of these frames. Instead you will get a `RepeatedFrames` object which summarises the information. See its docstring for more details.

Here is our updated implementation:

```python

def print_stack():

for frame_info in FrameInfo.stack_data(sys.exc_info()[2]):

if isinstance(frame_info, FrameInfo):

print(f"{frame_info.code.co_name} at line {frame_info.lineno}")

print("-----------")

for line in frame_info.lines:

print(f"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render()}")

for var in frame_info.variables:

print(f"{var.name} = {repr(var.value)}")

print()

else:

print(f"... {frame_info.description} ...\n")

```

And the output:

```

<module> at line 9

-----------

4 | def factorial(x):

5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)

8 | try:

--> 9 | print(factorial(5))

10 | except:

factorial at line 5

-----------

4 | def factorial(x):

--> 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)

x = 5

factorial at line 5

-----------

4 | def factorial(x):

--> 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)

x = 4

... factorial at line 5 (996 times) ...

factorial at line 5

-----------

4 | def factorial(x):

--> 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)

x = -993

```

In addition to handling repeated frames, we've passed a traceback object to `FrameInfo.stack_data` instead of a frame.

If you want, you can pass `collapse_repeated_frames=False` to `FrameInfo.stack_data` (not to `Options`) and it will just yield `FrameInfo` objects for the full stack.

Raw data

{

"_id": null,

"home_page": "http://github.com/alexmojaki/stack_data",

"name": "stack-data",

"maintainer": "",

"docs_url": null,

"requires_python": "",

"maintainer_email": "",

"keywords": "",

"author": "Alex Hall",

"author_email": "alex.mojaki@gmail.com",

"download_url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/packages/28/e3/55dcc2cfbc3ca9c29519eb6884dd1415ecb53b0e934862d3559ddcb7e20b/stack_data-0.6.3.tar.gz",

"platform": null,

"description": "# stack_data\n\n[](https://github.com/alexmojaki/stack_data/actions/workflows/pytest.yml) [](https://coveralls.io/github/alexmojaki/stack_data?branch=master) [](https://pypi.python.org/pypi/stack_data)\n\nThis is a library that extracts data from stack frames and tracebacks, particularly to display more useful tracebacks than the default. It powers the tracebacks in IPython and [futurecoder](https://futurecoder.io/):\n\n\n\nYou can install it from PyPI:\n\n pip install stack_data\n \n## Basic usage\n\nHere's some code we'd like to inspect:\n\n```python\ndef foo():\n result = []\n for i in range(5):\n row = []\n result.append(row)\n print_stack()\n for j in range(5):\n row.append(i * j)\n return result\n```\n\nNote that `foo` calls a function `print_stack()`. In reality we can imagine that an exception was raised at this line, or a debugger stopped there, but this is easy to play with directly. Here's a basic implementation:\n\n```python\nimport inspect\nimport stack_data\n\n\ndef print_stack():\n frame = inspect.currentframe().f_back\n frame_info = stack_data.FrameInfo(frame)\n print(f\"{frame_info.code.co_name} at line {frame_info.lineno}\")\n print(\"-----------\")\n for line in frame_info.lines:\n print(f\"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render()}\")\n```\n\n(Beware that this has a major bug - it doesn't account for line gaps, which we'll learn about later)\n\nThe output of one call to `print_stack()` looks like:\n\n```\nfoo at line 9\n-----------\n 6 | for i in range(5):\n 7 | row = []\n 8 | result.append(row)\n--> 9 | print_stack()\n 10 | for j in range(5):\n```\n\nThe code for `print_stack()` is fairly self-explanatory. If you want to learn more details about a particular class or method I suggest looking through some docstrings. `FrameInfo` is a class that accepts either a frame or a traceback object and provides a bunch of nice attributes and properties (which are cached so you don't need to worry about performance). In particular `frame_info.lines` is a list of `Line` objects. `line.render()` returns the source code of that line suitable for display. Without any arguments it simply strips any common leading indentation. Later on we'll see a more powerful use for it.\n\nYou can see that `frame_info.lines` includes some lines of surrounding context. By default it includes 3 pieces of context before the main line and 1 piece after. We can configure the amount of context by passing options:\n\n```python\noptions = stack_data.Options(before=1, after=0)\nframe_info = stack_data.FrameInfo(frame, options)\n```\n\nThen the output looks like:\n\n```\nfoo at line 9\n-----------\n 8 | result.append(row)\n--> 9 | print_stack()\n```\n\nNote that these parameters are not the number of *lines* before and after to include, but the number of *pieces*. A piece is a range of one or more lines in a file that should logically be grouped together. A piece contains either a single simple statement or a part of a compound statement (loops, if, try/except, etc) that doesn't contain any other statements. Most pieces are a single line, but a multi-line statement or `if` condition is a single piece. In the example above, all pieces are one line, because nothing is spread across multiple lines. If we change our code to include some multiline bits:\n\n\n```python\ndef foo():\n result = []\n for i in range(5):\n row = []\n result.append(\n row\n )\n print_stack()\n for j in range(\n 5\n ):\n row.append(i * j)\n return result\n```\n\nand then run the original code with the default options, then the output is:\n\n```\nfoo at line 11\n-----------\n 6 | for i in range(5):\n 7 | row = []\n 8 | result.append(\n 9 | row\n 10 | )\n--> 11 | print_stack()\n 12 | for j in range(\n 13 | 5\n 14 | ):\n```\n\nNow lines 8-10 and lines 12-14 are each a single piece. Note that the output is essentially the same as the original in terms of the amount of code. The division of files into pieces means that the edge of the context is intuitive and doesn't crop out parts of statements or expressions. For example, if context was measured in lines instead of pieces, the last line of the above would be `for j in range(` which is much less useful.\n\nHowever, if a piece is very long, including all of it could be cumbersome. For this, `Options` has a parameter `max_lines_per_piece`, which is 6 by default. Suppose we have a piece in our code that's longer than that:\n\n```python\n row = [\n 1,\n 2,\n 3,\n 4,\n 5,\n ]\n```\n\n`frame_info.lines` will truncate this piece so that instead of 7 `Line` objects it will produce 5 `Line` objects and one `LINE_GAP` in the middle, making 6 objects in total for the piece. Our code doesn't currently handle gaps, so it will raise an exception. We can modify it like so:\n\n```python\n for line in frame_info.lines:\n if line is stack_data.LINE_GAP:\n print(\" (...)\")\n else:\n print(f\"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render()}\")\n```\n\nNow the output looks like:\n\n```\nfoo at line 15\n-----------\n 6 | for i in range(5):\n 7 | row = [\n 8 | 1,\n 9 | 2,\n (...)\n 12 | 5,\n 13 | ]\n 14 | result.append(row)\n--> 15 | print_stack()\n 16 | for j in range(5):\n```\n\nAlternatively, you can flip the condition around and check `if isinstance(line, stack_data.Line):`. Either way, you should always check for line gaps, or your code may appear to work at first but fail when it encounters a long piece.\n\nNote that the executing piece, i.e. the piece containing the current line being executed (line 15 in this case) is never truncated, no matter how long it is.\n\nThe lines of context never stray outside `frame_info.scope`, which is the innermost function or class definition containing the current line. For example, this is the output for a short function which has neither 3 lines before nor 1 line after the current line:\n\n```\nbar at line 6\n-----------\n 4 | def bar():\n 5 | foo()\n--> 6 | print_stack()\n```\n\nSometimes it's nice to ensure that the function signature is always showing. This can be done with `Options(include_signature=True)`. The result looks like this:\n\n```\nfoo at line 14\n-----------\n 9 | def foo():\n (...)\n 11 | for i in range(5):\n 12 | row = []\n 13 | result.append(row)\n--> 14 | print_stack()\n 15 | for j in range(5):\n```\n\nTo avoid wasting space, pieces never start or end with a blank line, and blank lines between pieces are excluded. So if our code looks like this:\n\n\n```python\n for i in range(5):\n row = []\n\n result.append(row)\n print_stack()\n\n for j in range(5):\n```\n\nThe output doesn't change much, except you can see jumps in the line numbers:\n\n```\n 11 | for i in range(5):\n 12 | row = []\n 14 | result.append(row)\n--> 15 | print_stack()\n 17 | for j in range(5):\n```\n\n## Variables\n\nYou can also inspect variables and other expressions in a frame, e.g:\n\n```python\n for var in frame_info.variables:\n print(f\"{var.name} = {repr(var.value)}\")\n```\n\nwhich may output:\n\n```python\nresult = [[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [0, 2, 4, 6, 8], [0, 3, 6, 9, 12], []]\ni = 4\nrow = []\nj = 4\n```\n\n`frame_info.variables` returns a list of `Variable` objects, which have attributes `name`, `value`, and `nodes`, which is a list of all AST representing that expression.\n\nA `Variable` may refer to an expression other than a simple variable name. It can be any expression evaluated by the library [`pure_eval`](https://github.com/alexmojaki/pure_eval) which it deems 'interesting' (see those docs for more info). This includes expressions like `foo.bar` or `foo[bar]`. In these cases `name` is the source code of that expression. `pure_eval` ensures that it only evaluates expressions that won't have any side effects, e.g. where `foo.bar` is a normal attribute rather than a descriptor such as a property.\n\n`frame_info.variables` is a list of all the interesting expressions found in `frame_info.scope`, e.g. the current function, which may include expressions not visible in `frame_info.lines`. You can restrict the list by using `frame_info.variables_in_lines` or even `frame_info.variables_in_executing_piece`. For more control you can use `frame_info.variables_by_lineno`. See the docstrings for more information.\n\n## Rendering lines with ranges and markers\n\nSometimes you may want to insert special characters into the text for display purposes, e.g. HTML or ANSI color codes. `stack_data` provides a few tools to make this easier.\n\nLet's say we have a `Line` object where `line.text` (the original raw source code of that line) is `\"foo = bar\"`, so `line.text[6:9]` is `\"bar\"`, and we want to emphasise that part by inserting HTML at positions 6 and 9 in the text. Here's how we can do that directly:\n\n```python\nmarkers = [\n stack_data.MarkerInLine(position=6, is_start=True, string=\"<b>\"),\n stack_data.MarkerInLine(position=9, is_start=False, string=\"</b>\"),\n]\nline.render(markers) # returns \"foo = <b>bar</b>\"\n```\n\nHere `is_start=True` indicates that the marker is the first of a pair. This helps `line.render()` sort and insert the markers correctly so you don't end up with malformed HTML like `foo<b>.<i></b>bar</i>` where tags overlap.\n\nSince we're inserting HTML, we should actually use `line.render(markers, escape_html=True)` which will escape special HTML characters in the Python source (but not the markers) so for example `foo = bar < spam` would be rendered as `foo = <b>bar</b> < spam`.\n\nUsually though you wouldn't create markers directly yourself. Instead you would start with one or more ranges and then convert them, like so:\n\n```python\nranges = [\n stack_data.RangeInLine(start=0, end=3, data=\"foo\"),\n stack_data.RangeInLine(start=6, end=9, data=\"bar\"),\n]\n\ndef convert_ranges(r):\n if r.data == \"bar\":\n return \"<b>\", \"</b>\" \n\n# This results in `markers` being the same as in the above example.\nmarkers = stack_data.markers_from_ranges(ranges, convert_ranges)\n```\n\n`RangeInLine` has a `data` attribute which can be any object. `markers_from_ranges` accepts a converter function to which it passes all the `RangeInLine` objects. If the converter function returns a pair of strings, it creates two markers from them. Otherwise it should return `None` to indicate that the range should be ignored, as with the first range containing `\"foo\"` in this example.\n\nThe reason this is useful is because there are built in tools to create these ranges for you. For example, if we change our `print_stack()` function to contain this:\n\n```python\ndef convert_variable_ranges(r):\n variable, _node = r.data\n return f'<span data-value=\"{repr(variable.value)}\">', '</span>'\n\nmarkers = stack_data.markers_from_ranges(line.variable_ranges, convert_variable_ranges)\nprint(f\"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render(markers, escape_html=True)}\")\n```\n\nThen the output becomes:\n\n```\nfoo at line 15\n-----------\n 9 | def foo():\n (...)\n 11 | for <span data-value=\"4\">i</span> in range(5):\n 12 | <span data-value=\"[]\">row</span> = []\n 14 | <span data-value=\"[[0, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [0, 2, 4, 6, 8], [0, 3, 6, 9, 12], []]\">result</span>.append(<span data-value=\"[]\">row</span>)\n--> 15 | print_stack()\n 17 | for <span data-value=\"4\">j</span> in range(5):\n```\n\n`line.variable_ranges` is a list of RangeInLines for each Variable that appears at least partially in this line. The data attribute of the range is a pair `(variable, node)` where node is the particular AST node from the list `variable.nodes` that corresponds to this range.\n\nYou can also use `line.token_ranges` (e.g. if you want to do your own syntax highlighting) or `line.executing_node_ranges` if you want to highlight the currently executing node identified by the [`executing`](https://github.com/alexmojaki/executing) library. Or if you want to make your own range from an AST node, use `line.range_from_node(node, data)`. See the docstrings for more info.\n\n### Syntax highlighting with Pygments\n\nIf you'd like pretty colored text without the work, you can let [Pygments](https://pygments.org/) do it for you. Just follow these steps:\n\n1. `pip install pygments` separately as it's not a dependency of `stack_data`.\n2. Create a pygments formatter object such as `HtmlFormatter` or `Terminal256Formatter`.\n3. Pass the formatter to `Options` in the argument `pygments_formatter`.\n4. Use `line.render(pygmented=True)` to get your formatted text. In this case you can't pass any markers to `render`.\n\nIf you want, you can also highlight the executing node in the frame in combination with the pygments syntax highlighting. For this you will need:\n\n1. A pygments style - either a style class or a string that names it. See the [documentation on styles](https://pygments.org/docs/styles/) and the [styles gallery](https://blog.yjl.im/2015/08/pygments-styles-gallery.html).\n2. A modification to make to the style for the executing node, which is a string such as `\"bold\"` or `\"bg:#ffff00\"` (yellow background). See the [documentation on style rules](https://pygments.org/docs/styles/#style-rules).\n3. Pass these two things to `stack_data.style_with_executing_node(style, modifier)` to get a new style class.\n4. Pass the new style to your formatter when you create it.\n\nNote that this doesn't work with `TerminalFormatter` which just uses the basic ANSI colors and doesn't use the style passed to it in general.\n\n## Getting the full stack\n\nCurrently `print_stack()` doesn't actually print the stack, it just prints one frame. Instead of `frame_info = FrameInfo(frame, options)`, let's do this:\n\n```python\nfor frame_info in FrameInfo.stack_data(frame, options):\n```\n\nNow the output looks something like this:\n\n```\n<module> at line 18\n-----------\n 14 | for j in range(5):\n 15 | row.append(i * j)\n 16 | return result\n--> 18 | bar()\n\nbar at line 5\n-----------\n 4 | def bar():\n--> 5 | foo()\n\nfoo at line 13\n-----------\n 10 | for i in range(5):\n 11 | row = []\n 12 | result.append(row)\n--> 13 | print_stack()\n 14 | for j in range(5):\n```\n\nHowever, just as `frame_info.lines` doesn't always yield `Line` objects, `FrameInfo.stack_data` doesn't always yield `FrameInfo` objects, and we must modify our code to handle that. Let's look at some different sample code:\n\n```python\ndef factorial(x):\n return x * factorial(x - 1)\n\n\ntry:\n print(factorial(5))\nexcept:\n print_stack()\n```\n\nIn this code we've forgotten to include a base case in our `factorial` function so it will fail with a `RecursionError` and there'll be many frames with similar information. Similar to the built in Python traceback, `stack_data` avoids showing all of these frames. Instead you will get a `RepeatedFrames` object which summarises the information. See its docstring for more details.\n\nHere is our updated implementation:\n\n```python\ndef print_stack():\n for frame_info in FrameInfo.stack_data(sys.exc_info()[2]):\n if isinstance(frame_info, FrameInfo):\n print(f\"{frame_info.code.co_name} at line {frame_info.lineno}\")\n print(\"-----------\")\n for line in frame_info.lines:\n print(f\"{'-->' if line.is_current else ' '} {line.lineno:4} | {line.render()}\")\n\n for var in frame_info.variables:\n print(f\"{var.name} = {repr(var.value)}\")\n\n print()\n else:\n print(f\"... {frame_info.description} ...\\n\")\n```\n\nAnd the output:\n\n```\n<module> at line 9\n-----------\n 4 | def factorial(x):\n 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)\n 8 | try:\n--> 9 | print(factorial(5))\n 10 | except:\n\nfactorial at line 5\n-----------\n 4 | def factorial(x):\n--> 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)\nx = 5\n\nfactorial at line 5\n-----------\n 4 | def factorial(x):\n--> 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)\nx = 4\n\n... factorial at line 5 (996 times) ...\n\nfactorial at line 5\n-----------\n 4 | def factorial(x):\n--> 5 | return x * factorial(x - 1)\nx = -993\n```\n\nIn addition to handling repeated frames, we've passed a traceback object to `FrameInfo.stack_data` instead of a frame.\n\nIf you want, you can pass `collapse_repeated_frames=False` to `FrameInfo.stack_data` (not to `Options`) and it will just yield `FrameInfo` objects for the full stack.\n",

"bugtrack_url": null,

"license": "MIT",

"summary": "Extract data from python stack frames and tracebacks for informative displays",

"version": "0.6.3",

"project_urls": {

"Homepage": "http://github.com/alexmojaki/stack_data"

},

"split_keywords": [],

"urls": [

{

"comment_text": "",

"digests": {

"blake2b_256": "f17bce1eafaf1a76852e2ec9b22edecf1daa58175c090266e9f6c64afcd81d91",

"md5": "b5179fcd8825a72548eb97bf7d0d609b",

"sha256": "d5558e0c25a4cb0853cddad3d77da9891a08cb85dd9f9f91b9f8cd66e511e695"

},

"downloads": -1,

"filename": "stack_data-0.6.3-py3-none-any.whl",

"has_sig": false,

"md5_digest": "b5179fcd8825a72548eb97bf7d0d609b",

"packagetype": "bdist_wheel",

"python_version": "py3",

"requires_python": null,

"size": 24521,

"upload_time": "2023-09-30T13:58:03",

"upload_time_iso_8601": "2023-09-30T13:58:03.530734Z",

"url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/packages/f1/7b/ce1eafaf1a76852e2ec9b22edecf1daa58175c090266e9f6c64afcd81d91/stack_data-0.6.3-py3-none-any.whl",

"yanked": false,

"yanked_reason": null

},

{

"comment_text": "",

"digests": {

"blake2b_256": "28e355dcc2cfbc3ca9c29519eb6884dd1415ecb53b0e934862d3559ddcb7e20b",

"md5": "d04f7cda6589138e90691aec1edbf0d5",

"sha256": "836a778de4fec4dcd1dcd89ed8abff8a221f58308462e1c4aa2a3cf30148f0b9"

},

"downloads": -1,

"filename": "stack_data-0.6.3.tar.gz",

"has_sig": false,

"md5_digest": "d04f7cda6589138e90691aec1edbf0d5",

"packagetype": "sdist",

"python_version": "source",

"requires_python": null,

"size": 44707,

"upload_time": "2023-09-30T13:58:05",

"upload_time_iso_8601": "2023-09-30T13:58:05.479746Z",

"url": "https://files.pythonhosted.org/packages/28/e3/55dcc2cfbc3ca9c29519eb6884dd1415ecb53b0e934862d3559ddcb7e20b/stack_data-0.6.3.tar.gz",

"yanked": false,

"yanked_reason": null

}

],

"upload_time": "2023-09-30 13:58:05",

"github": true,

"gitlab": false,

"bitbucket": false,

"codeberg": false,

"github_user": "alexmojaki",

"github_project": "stack_data",

"travis_ci": false,

"coveralls": false,

"github_actions": true,

"tox": true,

"lcname": "stack-data"

}